Spezial 19

Über bwp@

bwp@ ... ist das Online-Fachjournal für alle an der Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik Interessierten, die schnell, problemlos und kostenlos auf reviewte Inhalte und Diskussionen der Scientific Community zugreifen wollen.

Newsletter

bwp@ Spezial 19 - August 2023 - Update Februar 2024

Retrieving and recontextualising VET theory

Hrsg.: , , , &

Vocational Education and Training needs a middle range theory – an exploration. History, difficulties and ways of developing a theoretical approach to VET

The following paper discusses the chances of a middle-range theory for VET. Existing theories are either not well known or are based on a weak conceptual foundation.

There is a mainly German tradition in defining, conceptualising and implementing VET as a theory. In the first part, we reconstruct this theoretically in the field of educational science-based approaches that emerged at the beginning of the 20th century. Since the late 1960s and 1970s, social science research flourished in this field, but marginalised the conceptual basis of Bildung and Beruf. This move was accompanied by an interdisciplinary expansion, but also by fatigue in the definition of central concepts of VET. This has also jeopardised the coherence of a VET research approach. However, we see an opportunity in the further development of a theory of VET that is not primarily rooted in one discipline, but still focuses on an educational perspective.

Berufsbildung braucht eine Theorie mittlerer Reichweite – eine explorative Perspektive. Geschichte, Schwierigkeiten und Wege hinsichtlich der Entwicklung einer theorie-basierten Berufsbildungsforschung.

Im folgenden Beitrag werden die Chancen einer Theorie mittlerer Reichweite für die Berufsbildung diskutiert. Die heutige Berufsbildungsforschung stützt sich kaum oder nur ansatzweise auf theoretische Grundlagen.

Es gibt allerdings eine hauptsächlich in Deutschland beheimatete Tradition, Berufsbildung als Theorie zu definieren, zu konzeptualisieren und umzusetzen. In einem ersten Teil rekonstruieren wir diese im erziehungswissenschaftlichen Bereich angesiedelte Perspektive, die zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts entfaltet wurde. In den späten 1960er und 1970er Jahren marginalisierte ein sozialwissenschaftlicher Forschungsansatz diese Theorien, die auf Bildung und Beruf beruhten. Damit einher ging eine interdisziplinäre Ausweitung, aber auch eine Ermüdung hinsichtlich einer Reaktualisierung zentraler Konzepte der Berufsbildung, welche auch die Kohärenz eines Berufsbildungsforschungsansatzes in Frage stellte. Wir sehen jedoch eine Chance darin, eine Berufsbildungstheorie weiterzuentwickeln, die nicht in erster Linie in einer Disziplin verwurzelt ist, aber dennoch auf eine pädagogische Perspektive sich ausrichtet.

1 Introduction

Does Vocational Education and Training (VET) need a theory? The question may come as a surprise, given that the current climate in social science research is more oriented towards conducting research on concrete and specific aspects, and less towards defining a broad theoretical orientation. The emphasis seems to be on research-based knowledge and on results, even on specific evidence, but not on theories. One could say that the time of grand theories is over (see also Büchter 2019). However, it would be naive to believe that research works without reference to theory. Every research activity is inscribed in a specific theoretical perspective that guides and influences the elicited results and findings.

Sharing this concern, there are also some authors who argue for the urgency of renewing the theory of VET in these times (see e.g. McGrath et al. 2022). From their point of view, it is particularly important to say precisely what kind of theory constitutes the background of any given research on VET. However, it quickly becomes clear that there is no single, widely shared theoretical approach in this domain. Today researchers from various academic disciplines (education science, sociology, economics, political sciences, psychology, etc.) are active in this field and approach VET from their disciplinary backgrounds.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of such a composite panorama of disciplinary-based research with various theoretical references? Should VET regain a sound and specific theoretical basis as a common ground? And how should this be done?

In what follows, we will attempt to answer these questions, firstly, based on a historical reconstruction of probably one of the earliest theorisations in the field and, secondly, by paving the way for a new VET theory, which would meet the current requirements of theory-building. It is important to note at the outset that the answers to these questions are contestable. Many researchers believe that a theory of VET would not be necessary and even impossible to define due to the very composite nature of the subject. Others consider the various but unconnected disciplinary approaches as an advantage. In the “Dictionary of Vocational and Commercial Education” (Wörterbuch der Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik), 2nd edition, there is only one article about “theories of vocational education and training”. The author states, that “if it is at all justifiable” to establish a theory of VET, one “should think of educational theoretical foundations” as developed in the beginning of 20th century in Germany (Heid 2006, 462). Only a few areas, such as vocational socialisation research and vocational teaching and learning, have reached in his eyes today a “noteworthy degree of maturity in theoretical development” (ibid., 462). Also, other handbooks, like the Handbook of Technical and Vocational Education and Training Research, do not problematise in depth the issue of theorisation of VET. In its appendix a keyword “theory of VET” is lacking. Instead, it lists a variety of research areas. In the preface the editors speak of many “insights”, but not of “theory” or “theoretical approaches”. Nevertheless, they state that the presentation of “VET research with all its domains” serves as a tool and makes it possible to distinguish the field from other research disciplines (Rauner/Maclean 2008, 9).

Clearly, in a field where each approach is limited to specific disciplinary questions and research methods, the current situation bears the risk of knowledge fragmentation. Meanwhile some researchers struggle to develop a broader interdisciplinary view, others feel comfortable in their disciplinary homes without a strong VET-specific theoretical core.

On the basis of a historical reconstruction, focusing on the rise of VET theory in Germany, we will reconstruct the formation of a theory, based in education. This brings us back to the concepts of “Bildung” and “Beruf”, which recontextualised and adapted to the contemporary context, could still provide the basis for a theorisation of VET. But this concept, linked to a pedagogical approach to VET and based on a mainly philosophical background, wouldn't be able to meet the broader demands of the field today. In the second part of our contribution, we therefore will explore an approach, which takes the originally pedagogical perspective into account but also integrates the multiple perspectives (political, economic, sociological, psychological), that characterise the field of VET research today.

The aim of our contribution is nevertheless modest. On the one hand, we would like to (re-)launch the debate and set out a number of assumptions on which a future theory could be built, as well as the expectations that we can formulate in relation to it. On the other hand, we would like to sketch a theoretical model which could be – in dialogue with the scientific community of VET research – developed further.

2 The rise of the German theory of Bildung for VET

The starting point of our reflections will be historical. In particular, we will show how the beginnings of a theorisation of VET can be traced back to debates on school and apprenticeship reform around 1900. In Germany, this theorisation was largely built around the concepts of “Beruf” and “Bildung” and the role they had to play within education. Therefore, a more pedagogical grounding is the starting point for VET theorisation. However, this first attempt of a theoretical foundation of VET has lost importance over the decades as the field has opened to other disciplines. The desire to accompany VET with the development of an appropriate theoretical framework was replaced by more pragmatic concerns about more specified aspects, with the emergence of terms such as ‘key qualifications’, ‘competence’ or ‘skills’, which marginalised and even replaced the terms ‘Bildung’ and ‘Beruf’. Since the 1970s, these terms have proliferated, aiming to overcome classical notions of Bildung and Beruf by introducing new concepts such as ‘competence development’ or ‘competence maturation’ (see Arnold 2012). These new approaches also reflect a gradual shift away from a comprehensive theoretical base. Sometimes authors claim a paradigm shift, e.g., from Bildung to competences, which also implies a different approach to research (Eder 2021).

2.1 The premises of a theorisation of the field: the reflections on the reform of traditional apprenticeship

The beginnings of a theorisation of VET can be traced to the decades around 1900 and beyond, when processes of reform of schools and apprenticeships were initiated in most Western countries. The debates about the need to reform this institution of guild origin laid the foundations for a conceptualisation of the field.

Indeed, these debates will define the object of VET and distinguish it from simple on-the-job training and, at the same time, from older institutions such as primary and general education. They will also identify the driving forces behind VET, which are based on economic, social and educational aims. Of particular interest is the debate in Germany which, among other things, led to the emergence of what has been called the ‘dual model of VET’ since the 1960s and which, as will be shown, developed around the notions of ‘Bildung und Beruf’.

The emergence of a theory of VET is closely linked to a discourse that problematised the working conditions of young workers and apprentices. In 1875, the German Association for Social Policy (“Verein für Socialpolitik”) published 16 reviews and reports on the situation of apprentices and on ways of reforming vocational education. This association of economists, which still exists today, advocated free trade and an education system that emphasised a high level of qualification for workers, fair pay and an increase in the quality of products (Brentano 1875, 124). The documented discussions and perspectives show that the so-called ‘social question’ (“soziale Frage”) was at the forefront of defining a new way of training apprentices. The aim was to strengthen the role of the apprentice in the modern factory. Lujo Brentano, one of the leading figures of this association, was also part of the current of ‘cathedersocialists’ (“Kathedersozialisten”), so called because of their academic proximity to reformist, but not revolutionary, social democracy. He argued against Adam Smith’s critique of apprenticeship that the vocational training system should not be dismantled, but renewed, by complementing, rather than replacing, the exclusive learning in the company with education in schools. The versatility of workers should be increased, as even sensible factory owners would emphasise. In such a combined system the apprentice would ‘really learn’ (ibid., 68). This socially motivated basis for vocational training was expanded in the following years to include a political dimension.

Georg Kerschensteiner, the prominent school reformer and internationally known activist for vocational education, also referred to Brentano, but also to Otto von Bismarck and the ‘social question’, in his award-winning book “Civic Education of German Youth” (Staatsbürgerliche Erziehung der deutschen Jugend), published in 1901. The political integration of young workers and apprentices should be a task that schools should be aware of, he argued in his first publication on vocational education, which was followed by many more and more refined publications and books. He is now regarded as one of the founders of German vocational education theory. Kerschensteiner’s influence, or traces of his thinking, can still be seen today in vocational education, learning field theory and the practical orientation of schools (see Sloane 2022).

The freedoms and rights granted to the people, such as universal suffrage, freedom of the press, freedom of marriage and freedom of trade, went hand in hand, he argued, with an increased need for education (Kerschensteiner 1966[1901], 7). Education through work based on vocations was, in his view, the central answer for young people (especially from the working class) to integrate into society. Therefore, it was urgent to develop in them the feeling of being “an active member of the whole” and to stimulate them to develop character and more knowledge in a later stage of life (ibid., 84).

Kerschensteiner tackled the existing German continuation schools after compulsory schooling (“Fortbildungsschulen”) as a lever for the integration of German youth. In order to make these schools attractive to young people, but also to legitimise further investments in education (for the public funding of such schools), he vocationalised (“verberuflichte”) this type of school in theory and practice in Munich (Gonon 1992). The entire vocational education system, i.e. the arts and crafts and industrial schools as well as the trade associations, should develop a “common spirit” (Kerschensteiner 1914, 151) and thus be able to educate citizens who, through their work, contribute to the well-being of the “politic body” (ibid., 153).

The first idea is to adapt young people to society. For this, they should also receive “Bildung”, but not in the Humboldtian sense, based on a mainly humanistic culture, but on a specific form of “character formation” (“Charakterbildung”) oriented towards work. Bildung should begin with manual activity, which later leads to a broader knowledge and personality. Moreover, this kind of education is bound up in a national consensus and enables not only the worker but all members of society to be part of a community (“Gemeinschaft”). In several of his writings Kerschensteiner emphasises this expression “Bildung of character”, which includes psychological dimensions such as will, judgement and sensitivity. A quotation underlines this “spirit” for the whole educational system, which he develops in his book “The Unitary German School System” (Das einheitliche deutsche Schulsystem):

what civic awareness (“Geist der Staatsgesinnung”) is, is the will, strengthened by insight and habit, to contribute to the welfare of not only individual social classes, but of all classes without exception, to cooperate in the development of a moral community ... and to do so in the place where vocation, inclination and fate have placed the individual. (Kerschensteiner 1922, 119).

In another publication, “The Notion of Character and Character Education” (Charakterbegriff und Charaktererziehung), he states that strong character is built through work and work communities (Kerschensteiner 1929). For Kerschensteiner, vocational work, especially in schools, is “the most appropriate means of civic education” (Gonon 2009, 76). Out of this process or act of education, the task and calling of the teacher and instructor can also be defined as a social form of life and work (Kerschensteiner 1949, 155). Kerschensteiner’s concern was not primarily to provide the economy with efficient workers, but to focus on the whole person (Kerschensteiner 1966 [1928], 149). The vocational school should be aware of two principles: not only to impart knowledge, but also to introduce practical skills and working methods; and secondly, not to isolate itself, but to integrate the vocational school into the life of the working community of which the individual learner should later become a member (ibid., 148). He also advocates the perspective of an educational pathway to higher education (ibid., 160).

In a way, it is not surprising that the development of German VET theory has been channeled into educational theory and in relation to the public education system. Beruf and Bildung, but also the organisation of learning and teaching in vocational education, are the main pillars of such a philosophically based approach. The two last books of Kerschensteiner's intensive publishing activity, which were not as influential as his earlier books, are a theory of Bildung (Theorie der Bildung) and a theory of organisation of Bildung (Theorie der Bildungsorganisation) (Kerschensteiner 1926, Kerschensteiner 1933). What is surprising to a modern reader today is that there is no notion of a dual apprenticeship system or a deeper analysis of workplace learning in relation to vocational schools. Instead, as Diane Simons rightly points out, the focus is on school and compulsory further education for all German young people (Simons 1966, 136). The main task of his last publication, according to the preface, is how the idea of Bildung can be realised in a limited time and in given structures. The definition of organising principles, which are aware of sociological and organisational problems, must be taken into account for the whole educational system, thus all educational institutions are or should not be too specialistic schools but rather “general vocational schools” (“allgemein bildende Berufsschule[n]”) (Kerschensteiner 1933, 185). In addition to Kerschensteiner, other pedagogues such as Aloys Fischer, Eduard Spranger and later Theodor Litt were involved in reflecting on and legitimising vocational education, as the first handbook for vocational schools (Handbuch für das Berufs- und Fachschulwesen) published at the end of the 1920s shows, which also dealt with the ethics and sociology of Beruf (Fischer 1929) and the characteristic of Bildung torn between general and vocational education (Spranger 1929). This handbook, edited by Alfred Kühne, the ministerial director in the Prussian Ministry of Trade and Commerce, shows the intertwining of education with the different types of (vocational) schools. In his introductory chapter, Kühne himself outlines the rise of a ‘new education (“neue Bildung”), which included the further development and integration of vocational schools into the education system, as well as a closer link between school and work, in order to allow the professional and political ideal of education to blossom in young people (Kühne 1929, 25).

The German discourse about extending Bildung by integrating vocational aspects as well as the school reform of Kerschensteiner, i.e., the Munich model of vocational schools, was also noticed in the US. Kerschensteiner’s Three Lectures on Vocational Education. Delivered in America under the Auspices of the National Society for the Promotion of Industrial Education (Kerschensteiner 1911), found a broad audience. However, the prominent school reformer and philosopher of education, John Dewey, with whom Kerschensteiner had several exchanges and even a personal meeting in New York in 1911, was skeptical about specific (and separated) schools for future workers and opposed such endeavours in the US.

For Dewey, the orientation towards vocations and industry should make school life more directly meaningful, and more connected to out-of-school experiences (Dewey 1997). In his seminal book Democracy and Education, Dewey, as in other publications, warns that vocational-technical education, as put forward in Germany, is too narrow and amounts to adapting to the industrial regime (Dewey [1913] 1944, 102). Thus, social differences are perpetuated. Vocational education and subjects should not be taught in separate schools, but should be integrated into mainstream schools, aiming at transforming economy and society. This transformative view implies an ethical understanding, which is the basis for a politically and institutionally defined democracy (Oelkers 2009).

Kerschensteiner’s view, however, was focused on the German nation, which should also include the working-class. His specific concept of education was derived from the German classics and the social policies of his time. In particular, it was Goethe’s figure of the craftsman as the core personality of work-based performance (Kerschensteiner 1910). Learning through craftsmanship and manual work was to be transferred to big industry, but also to the educational system. Goethe’s own life and Friedrich Schiller’s concept of aesthetic education should be models for learning in and out of school.

Eduard Spranger’s main contribution was the further development of Georg Kerschensteiner’s ideas on vocational schools and to transfer or enlarge his own concept of Beruf and Bildung. Spranger coined the expression “thinking hand” (“denkende Hand”) which should be the basis of VET (Spranger 1952). The vocational schools should be centered around vocations. The peasant, the artisan and the trader are in his view the three basic figures, not just as workers, but also as learners. VET therefore has to be based on such a kind of learning, which paves the way for Bildung and according to Spranger to a “higher self” (“höheres Selbst”) (see Gonon 2022).

All in all, the first generation of VET theory in Germany relied very much upon idealistic prerequisites, based on German classics like Goethe and Schiller. Furthermore, a discovery but also critical reassessment of Wilhelm von Humboldt was the specific achievement of Eduard Spranger (Spranger 1908). Bildung is not just introduced as a concept for universities or as an individual affair for a small elite, but as a core element that defines education and an education system. It is especially a second publication on Humboldt, which headed towards a ‘realistic Bildung’, that aimed at ‘humanising’ the existing education system (Spranger 1910, viii).

The aim of reflections and thinking of the reformers was to justify the expansion of a vocational education system and to increase the appreciation of vocational education in economy, society and science.

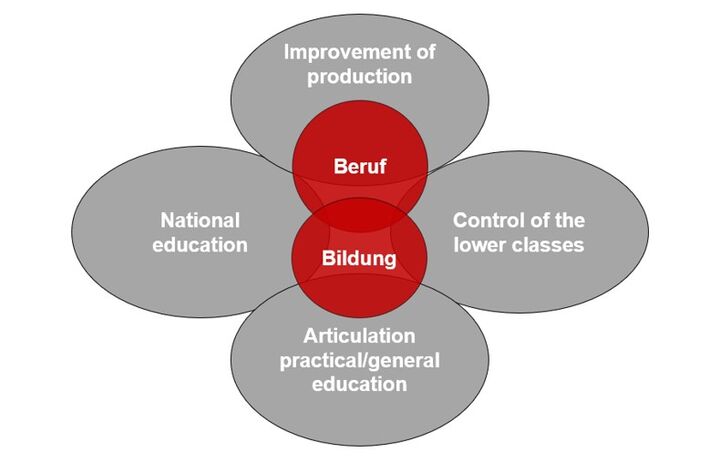

If we summarise the theoretical framework of the classical period in Germany we can put Beruf and Bildung in the center (see Figure 1). The concept is based on specific issues as they emerged in the political, economic, social and educational debate: national education (1), the willingness to integrate and control lower classes (2), the role or situatedness of practical or specific education and general education (3) and the will to provide a qualified workforce in order to improve production (4).

Figure 1: Beruf and Bildung as core of the classic VET theory

Figure 1: Beruf and Bildung as core of the classic VET theory

2.2 The attempt to modernise VET and VET theory

The theory of Bildung, including a vocational perspective, was already controversial before the Second World War. Anna Siemsen criticised the romantic notion of Beruf, which did not correspond to industrial reality (1926, 162 ff.). Another German philosopher and educationalist, Theodor Litt, also made a fundamental critique of such a foundation of VET theory. At the time of the reconstruction of West Germany, he also emphasised the importance of ignoring the technological basis and the development of industry and society, which endangered the theoretical foundations of the classics (Litt 1955). This aspect was reinforced in the early 1960s by educationalists and sociologists such as Karl Abraham (1957) and Heinrich Abel (1963). These authors pointed with urgency to industrial-technological development, to training in enterprises and to interactions within enterprises, which could no longer be neglected or ignored. In short, a renewal of VET and VET theory was at stake. Between the publication of two VET handbooks, one by Fritz Blättner and colleagues in the early 1960s (Blättner et al. 1960) and the other by Udo Müllges (including two volumes) in 1979, a shift towards a sociologically based perspective can be observed (Müllges 1979). Another approach was to adopt a political science perspective, as shown by Claus Offe’s pioneering study (Offe 1975).

On the one hand, the pivotal role played by the notion of Bildung was weakened, and on the other hand, there has been a spread over several disciplines in the sense that more and more disciplines have become interested in VET and have begun to study it. Both phenomena have had the effect of relativising the centrality of the educational approach centred on the notion of Bildung, and of spreading research in this field to many other scientific disciplines, with reference to specific theorisations.

Another more general trend in the 1960s within education, which affected educational science as a whole, was the claim for a more realistic turn (“realistische Wendung”), as announced by Heinrich Roth’s Inaugural Lecture at the University of Göttingen. He wanted to combine historical-philosophical reflection with more data-based research on the reality of education and its optimization in terms of educational policy (Roth 1962). In this respect a more empirically oriented research and a stronger orientation on the basis of social sciences took place. Lutz von Werder also postulated a paradigmatical turn toward VET and VET theory as “social science” (Werder 1976, 324).

New theory in Germany should be furthermore critical and not affirmative towards existing VET, as several authors argued. Karlwilhelm Stratmann criticized the authoritarian character of the master-apprentice-relationship, which leads to a permanent crisis of VET practice but also theory. He called for comprehensive reforms of the VET system in Germany (Stratmann 1967). Wolfgang Lempert focused on the lacking democratic and participative character in firms and focused in later studies on researching morality in the context of work-based training (Lempert 1971). From an international comparative perspective, Wolf-Dietrich Greinert analyzed the role of the dual apprenticeship system in Germany critically (e.g. Greinert 1993). All forementioned plead for an approach towards VET which aimed at modernization of VET and VET theory and included an emancipatory perspective, as it was also seen in the writings of the Frankfurt School (Gonon 1997).

Probably the most influential contributor to a renewed theory of VET, however, was Herwig Blankertz. He renewed the classical approach to Bildung, including vocational education. Around this discourse and the newly established schools at upper secondary level (“Kollegschulen”) with a programme of integration of general and vocational knowledge based on Blankertz’s concept, the expression “Bildung im Medium des Berufs” (“education through vocation”) was coined. Blankertz combined the classical ideas of Beruf and Bildung (inspired mainly by Kerschensteiner and Spranger) with a critical approach to society (as promoted by Jürgen Habermas and others) (Blankertz 1963). Such a theory of VET was quite normative and promoted an approach that integrated VET at the institutional level into the general and academic education system (Blankertz 1983). The opposite position was taken by Heinrich Abel, who in the early 1960s argued for sociology as the new guide for VET and VET research (Gonon et al. 2010, 435 f ). These reflections are still echoing today like in the position recently taken by Felix Rauner, who defined occupation and vocational science as the core of VET theory. The background is an empirical research programme with an interdisciplinary set of methods, which is organised around the criterion of “practical plausibility” (Rauner 2005, 14 f.). In addition to this approach, a psychological and didactic perspective has developed as a field of research that is very close to educational psychology and, later, to skills research, which has gained a certain presence in the German VET research landscape (Achtenhagen/Pätzold 2010).

The presented concepts and debates so far are located mainly in university and pedagogy. It has to be noticed, that the emergence of a pedagogical subdiscipline in the 1960s alongside the establishment of a teacher training for vocational schools on a higher education level – the German Association of Educational Research, Division Vocational Education (BWP - “Sektion Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik der DGFE”) – boosted the debate and research for VET. A further element of expanding VET research was the rise of several new founded research institutions and supporting structures for VET, like the Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training (Bundesinstitut für Berufsbildung, short BIBB – founded in 1970) and the CEDEFOP (European Center for the Development of VET founded in 1975) which started to do research in this field.

What can be observed is, that an original theoretical basis, which was the mark of the rising VET theory at the beginning of the 20th Century lost its coherence, when expanding during the next decades. Under the roof of educational science, which integrates itself several disciplinary perspectives, VET research and VET theory got more fragmented. A decisive element was also the “realistic turn” and the expansion of social sciences which also affected pedagogy but also other disciplines (see Gonon 1997). A consequence was the interdisciplinarity of VET research. Thus, a broader range of approaches, like history with a social focus, history of ideas, qualitative studies and also quantitative studies with an economic or sociological background, gained ground.

2.3 The post-68- debates: sociology of industry, key qualifications, competences and governance

A new and realistic approach to the economy and society also meant taking account of industrial and technological developments. In the 1970s, the role of the dual apprenticeship system was at the centre of a conceptualisation of VET. In addition, new concepts such as key qualifications, competence, standards and quality became more attractive. Nevertheless, the debate about the role of Beruf and the form in which VET should be organised and positioned, i.e. the perspectives of the dual apprenticeship system, remained important issues (see e.g., Kutscha 1992, 1992a). However, the concept of Bildung, or vocationally based Bildung faded. Task-oriented qualifications and vocational competence (“berufliche Handlungskompetenz”) came to the fore. This development was linked to the opening and broadening of research perspectives in VET. Industrial sociology, economy of education, psychological approaches brought in new concepts that seemed more applicable to empirical research. Political science also discovered VET and developed an international comparative approach.

In 1974 Dieter Mertens, the first director of the 1967 founded and still today very influential Institute for Employment Research (“Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung”, short IAB) launched a debate in proposing a new concept which he called “key qualifications” (“Schlüsselqualifikationen”) (Mertens 1974). He forwarded this concept as well as in his words a renewed or renewed idea of Bildung for the world of work. Key qualifications should adapt to the industrial development and technological change. The task for VET and the educational system was to guarantee the transferability of the learned knowledge, skills and attitudes.

In his seminal article “Bildung versus qualification” (“Bildung oder Qualifikation?”) Jochen Kade tried to merge these concepts in proposing “to direct both terms towards a universal understanding of work (Kade 1983).

The approach discussed fitted in well with the longer established research on qualifications, established by industrial sociology. Education, and in particular VET, had to adapt to industrial development and technological change, which were still based on VET and even a re-professionalisation of industrial tasks, which seemed to be threatened by Taylorist rationalisation (Kern/Schumann 1984).

Besides this (key-)qualification approach also the competence term, more precisely labelled as “professional action competence” (“berufliche Handlungskompetenz”) gained ground in the conceptualisation of theory and empirical research (Pätzold 2006).

A further boost for the establishment of a competence-based approach was given by the international comparative studies on the abilities of young people who have accomplished compulsory education. Since the 1990s a wide range of conceptual variations on competences as well as a lot of attempts to make vocational competences measurable have been established (e.g., Munz et al. 2012, Seeber/Nickolaus 2010).

In recent years, another strand has emerged, namely theories with a governance focus on VET in the context of comparative research on varieties of welfare states and capitalisms. Political science has also introduced somewhat different concepts such as skill formation, which are strongly linked to nation-specific political-economic systems (see e.g., Busemeyer/Trampusch 2012).

All in all, we can observe related to VET theory a development of opening and narrowing at the same time. This development is also reflected in newer handbooks on VET and recently re-edited and improved editions of former publications, which lack a specific theoretical section. Instead, one finds topics upon VET on a macro-, meso- and micro-level and articles about research methods, The Handbook of Vocational Education and Training Research (Rauner/Grollmann 2018), also published in slightly different version in English (Rauner/Maclean 2008), focuses exclusively, as it is announced in the title, on research but not on conceptual or theoretical foundations. The recently reedited Handbook VET (“Handbuch Berufsbildung”) as well is arranged around topics like structures, learning, competences, didactics, learning sites, and the professionalization of instructors and teachers, at least complemented by a chapter about internationalization and another about history of VET in Germany (Arnold et al. 2020).

This downsizing of theory based on Bildung and Beruf has several reasons. First of all, a critique of the classics of VET led to a marginalization of Kerschensteiner and others. They were seen as outdated, but also since the 1960s as politically suspicious since most of them and their successors in this tradition behaved in the context of the German eventful history opportunistic and adapted to the political situation of their times or even were staunch supporters of the Nazi-regime (see Kipp/Müller-Kipp 1994).

A more external development was the steady change and transformation of the economy which led away from its industrial core to the service industry. The classic form of Beruf eroded, which led also to a dissolution of vocational pedagogical thinking (Lisop/Schlüter 2009).

Another aspect is fatigue with the paradigm clashes between critical and so-called ‘positivist’ approaches that dominated the German VET debate in the 1960s and 1970s. Younger generations of VET researchers adhere to a more pragmatic and interdisciplinary approach to research, sometimes at the expense of a theoretical foundation. On the one hand, with the marginalisation of the classics, the educational science perspective in the early 1970s lost its common theoretical horizon; on the other hand, the interdisciplinary opening led to an expansion of questions within educational science as well as to an expansion of disciplinary actors interested in VET research. Under these circumstances, a solid theoretical base did not seem to be an urgent task.

3 In search of a (re-)new(-ed) VET theory

In this section we argue that a VET theory approach is needed to improve VET research and strengthen the visibility in practice and policy of VET. A theoretical approach, which finds resonance in the research community and in the field of VET, helps to explain phenomena concerning VET. VET research today can be described as an assemblage of several projects with hardly any correspondence to institutional structures. The main results today in VET research are produced in different disciplinary frames, e.g. educational science, sociology, economics, psychology, political sciences, which cannot be easily combined in order to get a largely shared knowledge on VET (see also Harney 2020, 644 ff.). Furthermore, there is also a certain blindness to a comprehensive theory of VET. The overall concept of VET, which was clearly a pedagogically defined project, has faded. We are witnessing the emergence of a fragmented field of research, with different theoretical approaches, often not centred on VET, but simply considering it as a case.

In this situation, the question is whether the originally educationally based VET theory should stress the disciplinary roots integrating the new concepts and new approaches or if VET theory should emerge out of a shared practice of topics, concepts, analytical frameworks and methods, giving up its educational roots. Both paths are worth exploring and are probably not contradictory.

We will stress a perspective which can somehow integrate disciplinary approaches and revalue explicitly the pedagogically based perspective on VET. This includes the idea of a theory of middle range. A middle-range theory is characterised by three aspects: a set of relatively simple ideas as an analytical framework, secondly core criteria designed to specific aspects of social reality and thirdly a program of explanation (Mackert/Steinbicker 2013).

In his critique on Talcott Parsons’ overall system functionalism, Robert K. Merton developed the project of a middle range theory to abandon a “grand” theory, which was in his eyes not very fruitful. He also opposed a data gathering approach without any theoretical foundations (Merton 1957). Merton’s hope was to develop a more general theory for sociology from such a foundation in a second step, but this was never realised (see Esser 2002, 146). One or more middle-range theories, also in the tradition of Max Weber, would precisely meet the expectations of generating new knowledge and explanations through an approach that includes elements of empirical research (Seifert 2016).

A middle range theory for VET starts with clarifying the object we are dealing with: What is VET (and what is not)? What are its objectives? What factors influence its functioning? Then, it is necessary to specify what we expect from a theoretical approach to VET. Such an approach could be described as a set of assumptions, arguments, values, methodological procedures and rules that would form the basis for explaining the practices of VET systems in general. A theory is thus a common reference that allows participants in a scientific community to start their research with a common background, to avoid misunderstandings and to provide more than just a description of a phenomenon. A shared theoretical approach should make it easier to get to the core issues of VET research and to ensure that the results are widely shared. It is, of course, an approach that needs to be regularly questioned and possibly modified to avoid getting stuck in only one possible perspective.

4 A middle-range theory for VET: analytical framework and categories aiming at an explanatory perspective of VET

Our attempt to renew the classical conception of VET by enlarging it in a multidimensional perspective is presented in Figure 2.

Fig 2: Revised and broadened theoretical approach to VET, based on aims and on interdisciplinary perspectives

Fig 2: Revised and broadened theoretical approach to VET, based on aims and on interdisciplinary perspectives

The first difficulty to clarify a theoretical basis is to define the contours of the object of our interest. The concept of VET is characterised by many different meanings, multiple uses and applications in different countries. The international definitions that currently exist, such as the one proposed by CEDEFOP[1], provide an initial basis for ensuring that we are talking about the same thing. But such definitions are often very general and over-emphasise the dimension of qualification for the world of work. Referring to the reflections on the concepts of Bildung and Beruf presented earlier, we propose a broader definition of VET as the learning of an occupation or profession, understood not only as the acquisition of technical-practical skills, but also as personal development and socio-professional integration. This definition preserves the specificities of the concepts of Beruf and Bildung, while recontextualising them in a more open theoretical framework, allowing the integration of other disciplinary perspectives and going beyond the German pedagogical tradition.

The second difficulty is to situate such vocational learning within an institutional order that makes it possible. A framework in which different actors interact to ensure the conditions for learning, be it the state, companies, trainees etc. These interactions will result in compromises in legal or regulatory provisions that guarantee a specific form of learning. This second step extends the traditional pedagogical approach by including the institutional and systemic dimensions of VET, which have developed significantly in recent decades (see Busemeyer/Trampusch 2012, Thelen 2004). In this respect, we advocate an institutionalist-systemic and governance-oriented dimension integrated in our theoretical approach of VET.

The third difficulty is to identify and reformulate the general aims of VET as embedded in VET systems at the international level. Three main purposes or aims can be identified, which have developed historically, influencing each other (see Bonoli/Gonon 2022):

- Economic aims include a wide range of purposes: improving competitiveness and/or providing enterprises with a skilled workforce and thus supporting economic growth.

- Educational aims cover among other things safeguarding and supplementing the basic knowledge of compulsory education, furthermore civic education and the promotion of vocational knowledge and skills and encouraging and providing access to higher levels of learning and training.

- Social policy aims comprise inter alia the integration into the labour market and society, including disadvantaged groups thereby contributing to the reduction of social inequalities.

These aims are not stable concepts but often in flux and contested by several actors. The process of coordination and justification itself is one of the constitutive elements of building and reforming VET systems (see Bonoli/Vorpe 2022).

This perspective allows us to describe different modes of learning an occupation and the specificities of different VET systems, furthermore, to note the institutional particularities, to highlight the emphasis of a variety of aims, and to underline how the balance between acquisition of technical-practical skills, personal development and socio-professional integration can be achieved differently.

At this level, we have already fulfilled some of the requirements for a middle range theory: we have a set of basic concepts that enable us to describe the field, we have an analytical framework that helps us to relate these concepts to each other, and we have a basis for explaining the choices and differences that designate the systems at an international level on the basis of different institutional settings.

The next difficulty is to integrate the many disciplinary perspectives (political science, pedagogy, sociology, economics, psychology) that characterise the field of VET today. These disciplinary contributions must be considered. They are a very important source of knowledge for VET. The challenge is however to move from an interdisciplinary but fragmented perspective to a multidimensional perspective in which these different disciplinary approaches are integrated as analytical perspectives in a unified model. In other words, we propose an approach anchored in a common theoretical base, around the notion of VET, which contributes in broadening the theoretical scope.

This theoretical approach, which integrates different (originally disciplinary) dimensions, completes our middle range theory. It offers a strong analytical and explanatory bridge, which can be based on work already done in other disciplines, but at the same time offers a coherent integration of this work, avoiding the risk of fragmentation.

5 Conclusion

We can see that the attempts to develop a coherent theory of VET were in a way successful for the legitimation and the rise of the German VET system. The programmatic was education beyond narrow vocational qualification. At the same time, it was about reforming the school system and vocational training. It was the pedagogically based philosophers with a humanistic approach, named “Geisteswissenschaften”, who developed this theory and could also anchor it in higher education and teacher training. After being established and the turn towards social sciences in the 1960s the cultural pedagogical approach or this humanities’ paradigm lost its powerful role.

The turn in the 1960s broadened the research focus and the disciplinary background of the researchers. Not a great aspiration anymore, but small projects and special foci were on the foreground. Theory was in the background of such studies. As we have shown, the interdisciplinary approach has its advantages but also its pitfalls. VET as a specific topic is going to be blurred. Diverse disciplinary approaches restrict and fragmentise research and a common understanding. As well the pedagogical questions seem to disappear (Münk 2012). That is why a new attempt is needed, to bundle research and theoretical approaches with a focus on VET, as a system but also as a specific kind of learning. A VET-specific theoretical aspiration, not as a grand theory but as a middle-range approach, would help to clarify notions and the research itself in aiming at developing further an explanatory perspective.

The number of studies in VET has risen, as also the German and international journals in the field of VET reveal. As well the demand for VET research from politics and practice is given and there are enough researchers motivated to do this research. The task of developing a new VET theory is to find a way to establish a shared concept of research beyond the disciplinary boundaries.

References

Abel, H. (1963): Das Berufsproblem im gewerblichen Ausbildungs- und Schulwesen Deutschlands (BRD). Braunschweig.

Abraham, K. (1957): Der Betrieb als Erziehungsfaktor. Freiburg. i.Br.

Achtenhagen, F./Pätzold, G. (2010): Lehr-Lernforschung und Mikrodidaktik. In: Nikolaus, R./Pätzold, G./Reinisch, H./Tramm, T. (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik. Bad Heilbrunn, 137-159.

Arnold, R. (2012): Ermöglichen – Texte zur Kompetenzreifung. Baltmannsweiler.

Arnold, R./Lipsmeier, A./Rohs, M. (Hrsg.) (2020): Handbuch Berufsbildung. 3. Aufl. Wiesbaden.

Blättner, F./Kiehn, L. (Hrsg.) (1960): Handbuch für das Berufsschulwesen. Heidelberg.

Blankertz, H. (1963): Berufsbildung und Utilitarismus. Problemgeschichtliche Untersuchungen. Düsseldorf.

Blankertz, H. (1983): Berufsausbildung als Prüfstein für die pädagogische Qualität des öffentlichen Unterrichtswesens. In zbw, 79, 803-810.

Bonoli, L./Gonon, P. (2022): The evolution of VET systems as a combination of economic, social and educational aims. The case of Swiss VET. In: Hungarian Educational Research Journal 12, (2), 1-12.

Bonoli, L./Vorpe, J. (2022): Staatliche Regulierung und Autonomie der Akteure im Schweizer Berufsbildungssystem aus historischer Perspektive. In: Bremer, H./Dobischat, R./Molzberger, G. (Hrsg.): Bildungspolitiken, Bildung und Arbeit. Wiesbaden, 127-147.

Brentano, L. (1875): Gutachten VII. In Verein für Socialpolitik (ed.): Die Reform des Lehrlingswesens. Sechzehn Gutachten und Berichte. Leipzig, 49-71.

Büchter, K. (2019). Kritisch-emanzipatorische Berufsbildungstheorie – Historische Kontinuität und Kritik. In bwp@36. Online: https://www.bwpat.de/ausgabe/36/buechter (10.05.2023).

Busemeyer, M./Trampusch, C. (Eds.) (2012): The Political Economy of Collective Skill Formation. Oxford.

CEDEFOP (2017): The changing nature and role of vocational education and training in Europe Volume 1: conceptions of vocational education and training: an analytical framework. Publications Office. Cedefop research paper; No 63. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.2801/532605

Dewey, J. (1997 [1916]): Democracy and Education. An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. New York.

Dewey, J. (1944 [1913]): Some Dangers in the Present Movement for Industrial Education. Middle Works, Volume 7: 1912-1914. Carbondale, 98-103.

Eder, M. (2021). Von der Bildungstheorie zur Kompetenzorientierung – Eine analytische Auseinandersetzung mit zwei zentralen Begriffen der Gegenwart und den Folgen eines Paradigmenwechsels. Bad Heilbrunn.

Esser, F. (2002): Was könnte man (heute) unter einer „Theorie mittlerer Reichweite“ verstehen? In: Mayntz, R. (Hrsg.), Akteure- Mechanismen – Modelle – Zur Theoriefähigkeit makro-sozialer Analysen. Frankfurt, 128-150.

Fischer, A. (1929 [1922): Ethik und Soziologie des Berufes in der Schulerziehung. In: Kühne, A. (Hrsg.): Handbuch für das Berufs- und Fachschulwesen. 2. Aufl. Leipzig, 43-60.

Gonon, P. (1992): Arbeitsschule und Qualifikation. Arbeit und Schule im 19. Jahrhundert, Kerschensteiner und die heutigen Debatten zur beruflichen Qualifikation. Bern.

Gonon, P. (1997): Kohlberg statt Kerschensteiner, Schumann und Kern statt Spranger, Habermas, Heydorn und Luhmann statt Fischer: Zum prekären Status der berufspädagogischen 'Klassik'. In :Arnold, R. (Hrsg.), Ausgewählte Theorien zur beruflichen Bildung. Baltmannsweiler, 3-24.

Gonon, P. (2009): The Quest for Modern Vocational Education – Georg Kerschensteiner between Dewey, Weber and Simmel. Bern.

Gonon, P. (2022): The legitimation of school‐based Bildung in the context of vocational education and training: The legacy of Eduard Spranger: In: Journal of Philosophy of Education, 56, (3), 425-437.

Gonon, P./Reinisch, H./Schütte, F. (2010): Beruf und Bildung. Zur Ideengeschichte der Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik. In: Nikolaus, R./Pätzold, G./Reinisch, H./Tramm, T. (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik. Bad Heilbrunn, 424-443.

Greinert, W.-D. (1993): The dual system of vocational training in the Federal Republic of Germany. Structure and Function. Eschborn.

Harney, K. (2020): Theorieansätze der Berufsbildung. In: Arnold, R./Lipsmeier, A./Rohs, M. (Hrsg.): Handbuch Berufsbildung. 3rd edition. Wiesbaden, 639-650.

Heid, H. (2006): Theorien der Berufsbildung. In: Kaiser, F./Pätzold, G.( Hrsg.): Wörterbuch Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik. 2. Aufl. Bad Heilbrunn, 460-462.

Kade, J (1983): Bildung oder Qualifikation? Zur Gesellschaftlichkeit beruflichen Lernens. In: Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 29, 859-876.

Kern, H./Schumann, M. (1984): Das Ende der Arbeitsteilung? Rationalisierung in der industriellen Produktion. München.

Kerschensteiner, G. (1966 [1901]): Staatsbürgerliche Erziehung der deutschen Jugend. In: Wehle, G. (Hrsg.): Kerschensteiner. Band I – Berufsbildung und Berufsschule. Paderborn, 5-88.

Kerschensteiner, G. (1966[1928]): Der Ausbau der Berufsschule im deutschen Bildungssystem. In: Wehle, G. (Hrsg.): Kerschensteiner. Band I – Berufsbildung und Berufsschule. Paderborn, 147-160.

Kerschensteiner, G. (1911): Three lectures on Vocational Education. Delivered in America under the Auspices of the National Society for the Promotion of Industrial Education. Chicago.

Kerschensteiner, G. (1914):The Reconstruction of the Trade Schools in Munich. In: Kerschensteiner, G. (ed.) The Schools and the Nation. Translated by C. K. Ogden. London, 130-153.

Kerschensteiner, G. (1921): Die Seele des Erziehers und das Problem der Lehrerbildung. Leipzig.

Kerschensteiner, G. (1922): Das einheitliche deutsche Schulsystem. 2. Aufl. Leipzig.

Kerschensteiner, G. (1926): Theorie der Bildung. Leipzig.

Kerschensteiner, G. (1929): Charakterbegriff und Charaktererziehung. 4. Aufl. Leipzig.

Kerschensteiner, G. (1933): Theorie der Bildungsorganisation. Leipzig.

Kipp, M./Miller-Kipp, G. (1994): Kontinuierliche Karrieren – diskontinuierliches Denken? Entwicklungslinien der pädagogischen Wissenschaftsgeschichte am Beispiel der Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik nach 1945. In: Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 40, 727-744.

Kühne, A. (1929 [1922]): Entwicklungsstufen der Berufserziehung in Deutschland. In Kühne, A. (Hrsg.): Handbuch für das Berufs- und Fachschulwesen. 2. Aufl. Leipzig, 1-26.

Kutscha, G. (1992): «Entberuflichung» und «Neue Beruflichkeit» - Thesen und Aspekte zur Modernisierung der Berufsbildung und ihrer Theorie. In zbw 88, 535-548. «

Kutscha, G. (1992 a): Das duale System der Berufsausbildung in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland – ein auslaufendes Modell? In Die Berufsbildende Schule, 44, 145-156.

Lempert, W. (1971): Leistungsprinzip und Emanzipation. Studien zur Realität, Reform und Erforschung des beruflichen Bildungswesens. Frankfurt a.M.

Lisop, I./Schlüter, A. (2009): Bildung im Medium des Berufs? Diskurslinien der Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik. Frankfurt.

Litt, T. (1955): Das Bildungsideal der deutschen Klassik und die moderne Arbeitswelt. Bonn.

Mackert, J./Steinbicker, J. (2013): Zur Aktualität von Robert K. Merton. Wiesbaden.

McGrath, S./Powell, L./Alla-Mensah, J./Hilal, R./Suart, R. (2022): New VET theories for new times: the critical capabilities approach to vocational education and training and its potential for theorising a transformed and transformational VET. In: JVET 74, 4, 575-596.

Mertens, D. (1974): Schlüsselqualifikationen. Thesen zur Schulung für eine moderne Gesellschaft. In: Mitteilungen aus der der Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung, 7, 36-43.

Merton, R. (1957): On Theoretical Sociology. Five Essays – Old and New. New York.

Müllges, U. (Hrsg.) (1979): Handbuch der Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik. Düsseldorf.

Münk, D. (2012): Bologna, Lissabon, der EQR und die pädagogische Perspektive. Von der Schwierigkeit eines Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogen in Europa das Pädagogische zu finden. In: Büchter, K./Dehnbostel, P./Hanf, G. (Hrsg.): Der Deutsche Qualifikationsrahmen (DQR). Bielefeld, 135-154.

Munz, C./Rainer, M./Portz-Schmitt, E. (2012): Berufsbiographische Gestaltungsfähigkeit als neue Schlüsselkompetenz. In: Westhoff, G./Jenewein, K./Ernst, H. (Hrsg.): Kompetenzentwicklung in der flexiblen und gestaltungsoffenen Aus- und Weiterbildung. Bonn, 141-150.

Oelkers, J. (2009): John Dewey und die Pädagogik. Weinheim.

Offe, C. (1975): Berufsbildungsreform – Eine Fallstudie über Reformpolitik. Frankfurt.

Pätzold, G. (2006): Berufliche Handlungskompetenz. In: Kaiser, F./Pätzold, G. (Hrsg.): Wörterbuch Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik. 2. Aufl. Bad Heilbrunn, 72-74.

Rauner, F. (2005): Handbuch Berufsbildungsforschung. Bielefeld.

Rauner, F./Grollmann, P. (Hrsg.) (2018): Handbuch Berufsbildungsforschung. 3. Aufl. Bielefeld.

Rauner, F./Maclean, R. (2008): Preface. In: Rauner, F./Maclean (eds.): Handbook of Technical Vocational Education and Training Research. Dodrecht, 9.

Roth, H. (1962): Die realistische Wendung in der Pädagogischen Forschung. In: Neue Sammlung Göttinger Blätter für Kultur und Erziehung, (2),481-490.

Schlögl, P./Dér, K. (Hrsg.) (2010): Berufsbildungsforschung – Alte und neue Fragen eines Forschungsfeldes. Bielefeld.

Seifert, A. (2016): Theorien mittlerer Reichweite aus Daten gewinnen. In QuPuG, 3, (1), 6-14.

Seeber, S./Nickolaus, R. (2010): Kompetenz, Kompetenzmodelle und Kompetenzentwicklung in der beruflichen Bildung. In: Nikolaus, R./Pätzold, G./Reinisch, H./Tramm, T. (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik. Bad Heilbrunn, 247-257.

Siemsen, A. (1926): Beruf und Erziehung. Berlin.

Simons, D. (1966): Georg Kerschensteiner. His thought and its relevance today. London.

Sloane, P. (2022): Re-reading Kerschensteiner today: Doing VET in German vocational schools – a search for traces. In: Journal of Philosophy of Education, 56, (3), 408-424.

Spranger, E. (1908): Wilhelm von Humboldt und die Humanitätsidee. Berlin.

Spranger, E. (1910): Wilhelm von Humboldt und die Reform des Bildungswesens. Berlin.

Spranger, E. (1929 [1922]): Berufsbildung und Allgemeinbildung. In: Kühne, A. (Hrsg.): Handbuch für das Berufs- und Fachschulwesen. 2. Aufl. Leipzig, 27-42.

Stratmann, K. (1967): Die Krise der Berufserziehung im 18. Jahrhundert als Ursprungsfeld pädagogischen Denkens. Ratingen.

Thelen, K. (2004). How institutions evolve: the political economy of skills in Germany, Britain, the United States, and Japan. Cambridge.

Werder, L. v. (1976): Zur Verwissenschaftlichung der Berufspädagogik – einige Thesen. In: Deutsche Berufsschule, 72, 323-335.

[1] VET is defined as “education and training aimed at providing people with the knowledge, know-how, skills and/or competences required in particular occupations or more broadly in the labour market” (CEDEFOP 2017).

Zitieren des Beitrags

Gonon, P./Bonoli, E (2023): The concepts of vocational competence and competency: False friends in international policy learning. In: bwp@ Spezial 19: Retrieving and recontextualising VET theory. Edited by Esmond, B./Ketschau, T. J./Schmees, J. K./Steib, C./Wedekind, V., 1-20. Online: https://www.bwpat.de/spezial19/gonon_bonoli_spezial19.pdf (30.08.2023).